Diff-Testing Solidity with Rust and Foundry

Contents

Introduction

Differential testing (or diff-testing for short) is a fuzzing technique which aims at detecting bugs by comparing two different implementations of the same algorithm and checking for inconsistencies in their output or execution.

In the context of Solidity smart-contract development, where optimizations in the form of gas usage reduction lead to cheaper blockchain transactions, diff-testing is particularly interesting. In order to optimize execution, blockchain programmers will often resort to implementing their algorithms in the low-level YUL language, with instructions closer to the final bytecode that gets interpreted by the EVM. Collections of libraries and tools such as Solady are even being developed to make maximum usage of YUL in common smart-contract use cases.

YUL, while allowing for great control over the stack and memory usage, is harder to write and comprehend, and also skips some of the safety checks that Solidity natively adds behind the scenes (like overflow checks in math operations). It comes to no surprise that diff-testing can greatly improve the developers’ confidence in their low-level and highly optimized implementations.

For such programs, diff-testing against a naive and trusted Solidity implementation is common practice. However, when it comes to algorithms written in Solidity, there isn’t always a way to efficiently compare the implementation against another. Sure, one could implement another version of the algorithm in Solidity to compare against, but there isn’t always one and naive/alternative approaches are not always easy to implement in the constrained EVM runtime.

If only we could compare algorithms in diff-testing between different languages…

Enter FFI

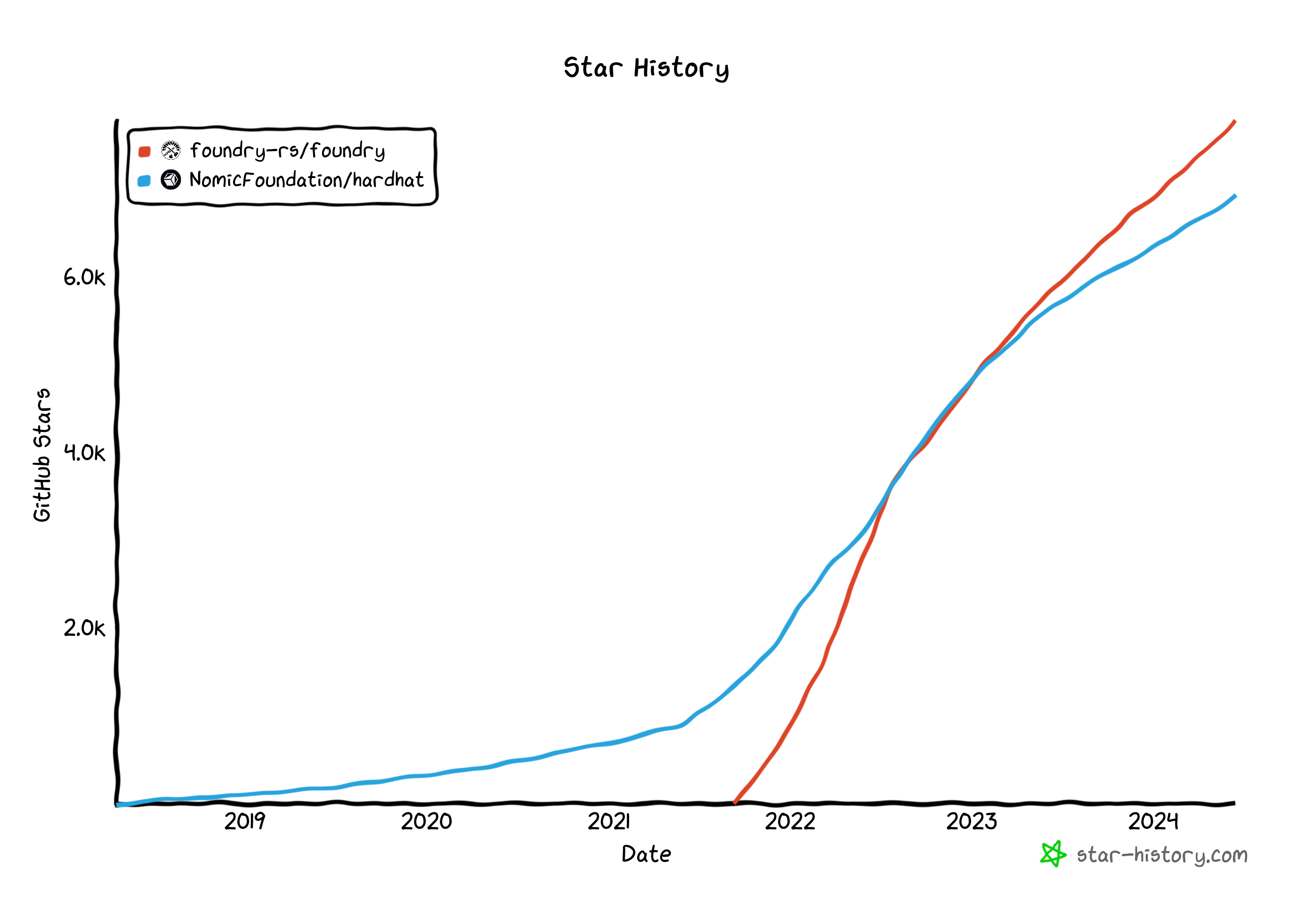

The Foundry development toolkit has transformed the developer experience of blockchain programmers since its inception in 2021, as seen by the wide adoption it got over the last couple of years. The ability to use the Solidity language across the full development cycle, from testing to deploying contracts is surely to thank for that.

One extremely powerful feature of the Foundry test utilities is its ability to call external binaries through a

Foreign Function Interface with the vm.ffi cheatcode.

function testFuzz_echo(uint256 rand) public {

string[] memory inputs = new string[](3);

inputs[0] = "echo";

inputs[1] = "-n";

// hex string representation of the random input in big endian

inputs[2] = vm.toString(bytes32(rand));

// command output (hexadecimal string) is parsed into bytes

bytes memory res = vm.ffi(inputs);

uint256 val = abi.decode(res, (uint256));

assertEq(val, rand, "comparing input and output");

}This opens up so many possibilities, from interaction with off-chain APIs, to the topic of today: diff-testing against an implementation in another programming language.

A Wild “Rust” Appears

It will be obvious to those who know me personally that my language of choice for implementing FFI test utilities (well, really, for implementing anything!) is Rust.

In the context of today however, Rust is particularly interesting because, it being a compiled language with a focus on correctness and performance, the startup times and memory footprint are relatively small, and the expansive crate ecosystem makes it a breeze to find good quality alternative implementations for many things.

Since diff-testing often relies of fuzzing the inputs to a particular function (i.e. generating random values), the test will be run many thousands of times. Each time, the Foundry suite needs to call our test utility once, to retrieve the output of the reference implementation. If the executable were to have a slow startup time, this would dramatically increase the time spent running our test.

Testing Overhead

The above example calling the echo command takes 192ms on my machine for 256 fuzzing runs. Compared to this,

the same test which doesn’t call echo (but performs otherwise all the same operations of building the array in memory

and the assert) takes 9ms. The FFI test is a noticeably slower of course, which is why we have to make our

executable as fast as possible.

Project Setup

Let’s setup a project to demonstrate some basic uses of the techniques described above. First, we create a new Foundry project and initiate a Rust project inside:

forge init diff-testingcd diff-testingcargo new utilsSince we want to be able to invoke cargo commands directly from the root of the diff-testing project and have the

built binary reside inside the target/release folder, we will add a Cargo.toml file at the root:

[workspace]

resolver = "2"

members = ["utils"]Now, running the following inside our project should compile and run the Rust binary in release mode:

cargo run -qrHello, world!Example: Solady’s DateTimeLib

As a practical exercise, we will differentially test the timestampToDate function implemented by Solady’s DateTimeLib library.

We add the Solady dependency to the project:

forge install Vectorized/soladyRust reference implementation

Let’s start by creating our reference implementation in Rust. We first add a dependency on alloy-core for

Solidity types and ABI encoding, and chrono for date/time manipulations:

cargo add -p utils chrono alloy-core -F alloy-core/sol-typesWe then add the following to our utils/src/main.rs:

use std::env;

use alloy_core::{

primitives::{Bytes, U256},

sol_types::SolValue,

};

use chrono::{DateTime, Datelike};

fn main() {

let args: Vec<String> = env::args().collect();

// the first argument (after binary name) is a command name

// this allows us to implement multiple test helpers in the same binary

match args[1].as_str() {

"timestamp_to_date" => timestamp_to_date(&args[2]),

// "another_command" => another_function(&args[2], &args[3]),

_ => {

panic!("invalid command")

}

}

}

fn timestamp_to_date(timestamp_str: &str) {

let timestamp: i64 = timestamp_str.parse().expect("timestamp should be i64");

// parse timestamp

let datetime = DateTime::from_timestamp(timestamp, 0).expect("timestamp should be valid");

// retrieve year, month and day

let data = (

U256::from(datetime.year()),

U256::from(datetime.month()),

U256::from(datetime.day()),

);

// ABI-encode

let bytes = data.abi_encode_params();

let bytes: Bytes = bytes.into();

// Print abi-encoded data as hex string without a line return at the end

print!("{bytes}");

}A few remarks about the code above. First, we parse the command-line arguments and discard the first one (0th index),

then use the next one as a command name, which allows to implement multiple helpers in the same binary. The next

argument will be a string representation of a signed 64-bit integer. The timestamp gets parsed as a DateTime and the

year, month and day are then ABI-encoded into a tuple of 3 unsigned 256-bit integers.

When we invoke our binary, we should see the following:

cargo build -rtarget/release/utils timestamp_to_date 17172000000x00000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000007e800000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000060000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000001Benchmarking this command with hyperfine gives us an average execution time

of 298μs on my system. Not too bad! For 256 fuzzing runs, this would translate to a total time of roughly 76ms, not

accounting for the overhead of the vm.ffi call.

Foundry Test

Let’s now create the fuzzing test in the Foundry project which will call the Solady implementation, the Rust binary, and compare the results.

function testFuzz_soladyTimestampToDate(uint256 timestamp) public {

// the `chrono` rust crate is limited to this maximum timestamp

timestamp = bound(timestamp, 0, 8210266876799);

string[] memory inputs = new string[](3);

inputs[0] = "target/release/utils";

inputs[1] = "timestamp_to_date";

// base-10 numeric representation of the timestamp

// i.e. if the timestamp were 42, then this would be "42"

inputs[2] = vm.toString(timestamp);

// get the reference result

bytes memory res = vm.ffi(inputs);

(uint256 refYear, uint256 refMonth, uint256 refDay) = abi.decode(res, (uint256, uint256, uint256));

// Solady's result

(uint256 year, uint256 month, uint256 day) = DateTimeLib.timestampToDate(timestamp);

// they should be equal

assertEq(year, refYear, "year");

assertEq(month, refMonth, "month");

assertEq(day, refDay, "day");

}

chrono crate. In

practice however, it would be good to test the full range of acceptable values according to Solady's own limitations.And here’s the result. Seems our test is even faster than the echo example we’ve seen before! 🎉

forge test --ffiRan 1 test for test/Diff.t.sol:DiffTest

[PASS] testFuzz_soladyTimestampToDate(uint256) (runs: 257, μ: 13136, ~: 12816)

Suite result: ok. 1 passed; 0 failed; 0 skipped; finished in 131.61ms (131.39ms CPU time)

Ran 1 test suite in 135.05ms (131.61ms CPU time): 1 tests passed, 0 failed, 0 skipped (1 total tests)Note that we added the --ffi argument to forge test to enable the feature. This could also be enabled by default

via the foundry.toml configuration file:

[profile.default]

src = "src"

out = "out"

libs = ["lib"]

ffi = trueConclusion

In this short article, we’ve seen how we can use Foundry’s FFI feature to perform differential testing with a reference implementation in Rust. This allowed us to verify the correctness of a low-level implementation without adding too much overhead to the test suite execution.

I hope you found something useful in this piece and that you’ll come back for more articles! Thanks for reading.